When unexplained incidents plague a Miami warehouse that supplies tacky Florida souvenirs, employees and investigators grapple with the zaniest alleged poltergeist on record while discovering rich Cuban culture and the biases against it. Told through a treasure trove of personal accounts and archival records.

October 1966. Miami, Florida.

Julio Vasquez, a handsome nineteen-year-old with dark hair and a great singing voice, dreamed he had been shot. He fell to the ground, his vision went black. Then, like a dream within a dream, he could see his own funeral, his body in the casket. Mourners congregated, but his mother was missing. She was still in Cuba, from which he had emigrated when he was eleven. Without her, Julio always felt incomplete. That sadness seeped into his nightmares.

In the three months prior, something seemed to be happening to Julio from the inside out. He had chicken pox, measles, and mumps. He developed what he described as “an excessive appetite.” Now came the nightmares, as if his unconscious were turning against him too.

He woke up and lay in bed, but what he would later describe as “some force” compelled him to leave his room. He went outside into the night. Julio was not sleepwalking but felt that unknown force compel him to drowsily wander Miami, a city that could be as surreal as a dream. Some nights, he followed 25th Street to the Biscayne Bay, where he stared into the dark horizon of the sea. The dazed night wanderings put Julio in danger as he crossed streets while cars zoomed past, and as he wobbled on bridges over rough waterways. He would snap out of it in time to get home, where he had to wonder why it was happening. His stepmother, his dad’s new wife with whom Julio never got along, would have preferred that he never return.

Julio was ready for the next stage of his life, ready to find enough financial independence to commit to his girlfriend, Maria, but the nightmares and the wanderings seemed to pull him back. By the end of the year, Julio gave in to his stepmother’s demands that he leave his father’s home. He moved in with a friend. He was on his own.

He was looking for some relief, but his nightmares would only get worse. And the chaotic, yearning, sometimes absurd nature of those vivid apparitions was about to show up in his real life, too.

Eight Months Earlier: Miami, Florida.

Rubber alligators and daggers. Key chains. Shot glasses. Palm tree salad tongs. Sailfish and flamingo ashtrays. Plastic backscratchers.

Tropication Arts was a wholesaler that supplied tropical novelties, gag gifts and souvenirs to the Florida kitsch market. In addition to the inventory they had shipped in, their own artists crafted original tchotchkes adorned with artwork and designs, including palm trees, waves and dolphins. Items would then be sent off from the warehouse to be sold at sidewalk stores, beachfront kiosks, gift shops and drugstores to fill the whims of tourists looking to pick something up for a few bucks. The company’s name added to the farcical nature of the novelties: “tropication” is not a word.

In the spring of 1966, Al Laubheim, 60, a hefty, balding man always puffing cigars, looked over his expanding fiefdom of tacky trinkets at 117 N.E. 54 St, where they had relocated weeks earlier. The 90-foot-long building had a front section for the bookkeeper and the painters to work, and sliding doors at the other end of the warehouse opened onto an alley for trucks to make deliveries. Besides Al’s office, the rest of the space was devoted to storage, where inventory was organized by Julio Vasquez, his astute but moody shipping clerk.

In the weeks after Tropication Arts moved in, the excitement of expansion was interrupted by an apparent break-in. The warehouse’s back doors were found open, but as police reported, “all the marks were on the inside of the doors, [not] as if the place had been broken in—as if it had been broken out of.” Police and Al were befuddled, and the investigation was never resolved.

Meanwhile, Al hired more staff to help Julio keep track of inventory. This included young workers excited for their first jobs, like Barbara Singleton, 14, who took on some hours after school. Employees loved Al (which is what he asked them to call him), an Army veteran with a lively sense of humor and blue-collar sensibility. He worked as a repairman for a Manhattan taxi company before moving to Florida and entering the novelty business with partners.

Tropication Arts could be a zany, entertaining place to work. Center stage was Lisa, Al’s pet squirrel monkey. Lisa would duck and dart all around the warehouse, knocking over merchandise. Boxes would spill into the aisles and beer mugs would break. Glen Lewis, Al’s hard-nosed business partner, would yell: “Lisa, stop it!” Al’s admonitions were gentler: “Lisa, please quit breaking things. You’re running us out of business.”

One day, Lisa got her hand on an egg and smashed it on Al’s head. He was more entertained than angry, but Lisa bounded away—and a day later, was nowhere to be seen. “Lisa, where are you?” he asked. “Please break just one more beer mug. We miss you.”

At first, Al thought Lisa might have been hiding in the warehouse, but as time wore on it was clear that she had likely slipped out to the street and was lost. She would never survive on her own.

Julio at the warehouse.

Lisa’s disappearance occurred around the time that stock clerk Julio’s nightmares began. The nightmares coincided with another strange occurrence: warehouse employees started to smell smoke but “couldn’t find where it was coming from.” Even stranger, mugs would fall off their shelves seemingly at random, the costs having to be tallied in the ledger books by the bosses.

“Nobody paid much attention,” Ruth May, one of the painters at Tropication Arts, later lamented. It was as if working in a souvenir shop had dulled the workers’ sensitivity to the unusual.

One person did take it seriously. Barbara, the high schooler with a part-time gig, worked for a single week and “didn’t like what she saw.” She left on a Friday afternoon. Paychecks were distributed on Monday, but she did not return for hers–scared, it seemed, by something she felt or saw.

Four months into his recurring nightmares, Julio Vasquez was frustrated with his Tropication job. His boss, Al, was encouraging and protective of his employees, but the other owner, Glen, was a pain, implementing a new system for the shipping clerks that Julio found unnecessary. Glen’s oversight seemed to be an excuse to assert control. The business did well—bringing in $200,000 the previous year, a substantial sum in the late 1960s—but the employees didn’t reap benefits. Pay held steady at $60 for 40 hours of work. Vacation was unpaid. Instead of a Christmas bonus, Julio was offered the choice of any item in the shop, a practically worthless gift. He opted for the joke refrigerator stickers.

Julio couldn’t quit unless he found another position, especially now that he had moved out of the home of his father and stepmother. It was not just about losing a stable place to live but about losing his father in his life, at least for now, making the longtime absence of his mother sting even more. He began to act out at work, coming in as late as noon some days.

He was also becoming more wary of the strange incidents at Tropication, like the phantom smoke and the falling mugs, which were becoming impossible to ignore.

Iris Roldan, 18, a petite and soft-spoken Latina shipping clerk at Tropication Arts, always had a stamp in her hand, decorating each item FLORIDA. While she and Julio were talking one day at Iris’ desk, a shot glass crashed on the floor from a shelf 20 feet behind them, shattering at their feet. The only person in the warehouse at the time, Curt, another shipping clerk, was nowhere near the glass, and the distance and trajectory the object had moved seemed impossible by any definition of physics.

There was more to come. Three beer mugs shattered while on a shelf with nobody in sight. A full glass of water that had been on a desk launched to the floor ten feet from where it was resting while Julio, Iris and Curt were at the other side of the warehouse.

The employees had a useful resource in the form of boxes of novelty spy glasses on hand to examine all corners of the warehouse, but nothing was spotted that could have been the cause of bric-a-bracs raining down around them. While commiserating with Julio, Iris “saw a big cardboard carton start to move by itself.” The carton fell to the floor, and Iris ran out of the building, “screaming and crying.”

Bea Rembisz, 49, had seen enough. She’d worked as an artist for Al for 20 years. At first, she tried to keep a sense of humor about the incidents, but that didn’t last. The afternoon that Iris ran out crying, the radio in the warehouse was tuned to the “Talk of Miami” on WKAT Miami Beach, 1360 on the AM dial. The guest on the afternoon show was a woman named Susy Smith, a local writer who was researching a book on American ghosts and paranormal events.

Bea got through to the station. Soon, she was on air. She talked about the flying beer mugs and shot glasses. What had started as an annoyance had now caused real alarm. How, she asked, could they make it stop?

“Just hang on and keep calm until I can get out there,” Susy told Bea.

Friday the 13th was as good a day as any to meet a poltergeist in South Florida. The region, much of which hovered over once-impassable ancient swamps, was filled with buildings and neighborhoods that had been abandoned and rebuilt over endless economic downturns and recoveries. From its earliest days, Miami attracted people worldwide who brought their own religions and superstitions, creating a colorful hodgepodge of belief systems.

Susy Smith, 55, arrived at the busy Tropication Arts at 11:30 am the next morning, her black portfolio in hand. On the inside cover: a hex sign to ward off evil.

“Life was one long scream to me,” was how Susy reflected on her path to becoming a paranormal writer and investigator. In her twenties, Susy was diagnosed with blood poisoning as the result of untreated strep throat. The infection traveled to her hip. Doctors were convinced she would die, and friends said goodbye.

Susy survived, but, as she later recalled, “the infection had eaten away so much of the bone that there is only a very shallow hip socket and a tiny head to the femur left.” Surgery was followed by recovery and improvement, but physical and mental trauma persisted for years to come.

While working as a journalist in Salt Lake City, Susy longed to feel a deeper connection with the memory of her late mother. She asked a friend to borrow her Ouija board, “and with that step I opened my own personal Pandora’s box and let myself in for the most hazardous adventures of my life.”

Susy, aided by a cane since her surgery (“a cane really isn’t so bad once you’ve made friends with it,” she’d say), traveled the country making inquiries into unexplained phenomena at a time when women were doubted and marginalized in the field of parapsychology. Susy sometimes reflected on how her struggles with her physical and mental health ultimately strengthened her ability to engage with paranormal beliefs and claims. She believed her disabilities compelled her to extend their senses beyond her body, and to seek and recognize a world beyond her own skin.

Considered a talented medium, Susy was tested and trained at the famed Parapsychology Laboratory at Duke University, where she connected with other leading investigators.

Susy perked up when she listened to Bea’s details of what had happened during the radio call-in.

She later wrote: “It isn’t often that a spook sleuth in the midst of writing a book about ghosts is lucky enough to have a genuine poltergeist case fall right into her lap.”

In the foyer of Tropication Arts’ warehouse, Susy was greeted by Ruth May, who reiterated the paradox of their situation: “I don’t believe it, but it’s really happening. I saw it with my own eyes.” Ruth May brought her to Al. The affable owner echoed his employee, saying “I don’t believe in ghosts” while shaking her hand. When they unlocked their doors for the morning, they discovered a mess of open boxes: foam rubber baseballs, salt and pepper shakers, ashtrays, and pencil cases. Al summed things up: “Something we can’t see is making a shambles of our warehouse.”

Susy Smith’s witness interviews.

With the eye of a newspaper reporter, Susy approached the case by verifying facts as soon as they happened. She couldn’t rule anything out at first. In a workplace like Tropication Arts, with the malaise of long days and tired employees, someone could have decided to wreak havoc. However, the employees were in close quarters and could easily see what each of the others was doing, and the notion of two or more conspiring to put Al and Glen out of business by breaking the same merchandise that enabled the employees to get their paychecks, while not impossible, was far-fetched.

“Poltergeist” meant “noisy ghost” in German and evoked a contained space in which everyday objects were disrupted and manipulated by an unseen force. In parapsychology literature, purported poltergeists were expected to be found in a domestic setting. A report of occurrences in a workplace was highly unusual, making the case all the more worthy of investigation.

While Al was reviewing details with Susy, they became distracted by a sound from the warehouse. They went to find the source. A box of plastic pencil sharpeners— shaped like miniature TV sets—had spilled open between two shelves. The employees, who huddled together, all said the same thing: “It just fell, all by itself!” It was the first of more than 300 incidents Susy would document.

Minutes later, Susy saw a box of plastic fans fall from a shelf. She examined the shelf. It was “smooth and dry,” without wires, ropes or any other mechanism that could be pulled. After lunch, Susy sat next to one of the tables where the artists worked on their creations and took in the view. Tropication Arts felt like a self-enclosed world of its own, a kind of snow globe–or, the Florida version, a sand globe, like the ones Tropication sold. A microcosm of Florida, the urge to make money among the warehouse team mingled with a desire for relaxed socializing. Also like Florida itself, a touch of absurdity was never far. Susy noticed that after Julio and Curt finished organizing boxes, Glen would often reorganize them when they were looking away, leading to comical confusion when the clerks returned to the same shelf.

The afternoon proved hectic. A box of rubber daggers fell, and while everyone rushed over to investigate, a sailfish ashtray smashed onto the ground—on the other side of the warehouse from where they were all together examining the daggers.

Susy barely had enough time to start her notes when a box of imitation leather coin purses scattered in multiple directions.

Glen thought that Susy was a distraction who was making things worse. “It’s not the end of the world,” he’d say when something shattered or fell. They were all “wasting time” worrying about it, while his refrain was, “we have work to do.” He insisted on order above all else.

Susy struggled to make sense of the events. Unable to sleep, she called William Roll, a friend who ran Duke University’s Parapsychology Laboratory devoted to studying unexplained phenomena. An Oxford-trained psychologist, Roll had the scientific acumen to complement her investigation. Roll was away due to a death in the family, so Susy was still on her own.

Julio saw chaos escalate at Tropication Arts. As objects broke left and right, he had to rush to clear the mess. At one point, while sweeping the ashtray shards into a dustbin, a shot glass crashed to the ground right behind him, as though a missile aimed for him.

Julio confided in Susy that he wanted to quit. He had enough unexplained moments caused by his nightmares, he didn’t need more at work. He was nearly trembling when talking about the bizarre phenomena, and then there were other issues like Glen’s unfair management style. Susy did her best to help keep Julio calm, and it would fall to Maria outside the warehouse to reassure him that everything would work out. But he had to find his way to leave. Though he longed to sing with a band, he cobbled together practically all the money he had to sign up for a class at an IBM school, an escape hatch from Tropication and a way to show Maria he was serious about their future.

Meanwhile, Al was impatient and more scared than he admitted. Worried about the real possibility of someone getting hurt in the warehouse (and the liability that could follow), and knowing Julio and the rest of his employees could flee at any moment, Al thought it best to place the events on record by contacting the police. Al said plainly that he had a ghost in his place of business, and the ghost was breaking his merchandise.

Bill Houghton, the complaint clerk, had received the phone call.

“You are going to think I’m drunk,” Houghton told Patrolman William Killin. Houghton explained the call. Killin responded: “This guy has got to be a nut.”

Killin arrived at the warehouse and met Al. “You are not going to believe a word I say,” Al warned, adding: “You are going to see an incident happen.”

Killin laughed off the prediction. He followed Julio and Al around the warehouse. At that point, they were alone in the building. While walking down an aisle, Killin saw a so-called “zombie” glass—a tall glass used to serve cocktails—fall and shatter. The patrolman paused. There was nothing visible that could have caused it. Killin couldn’t deny what he’d seen. How could he write up a police report about a possible ghost? At another point in the warehouse, a glass bottle bounced a foot into the air three successive times.

Killin called his supervisor. “You’d better come over here, sir. There’s something mighty strange going on.” Sergeant William McLaughlin asked if Killin could save him a trip and just explain on the phone. “If I handed him the report without him being there and seeing it,” Killin would later recall, the sergeant “would [have] had me up at the [mental] institute.” Killin urged his boss to come in person.

McLaughlin arrived, joined by two other patrolmen, Officers David J. Sackett and Ronald Morris. Both of the latter officers saw boxes tumble down while at the warehouse. “I’ll shoot the next thing that moves,” McLaughlin said, one of the few cops on record in parapsychology history to threaten shooting a poltergeist. Killin, meanwhile, was immediately harassed about his earnest belief in the incidents. Some officers called him “Casper the Friendly Ghost.” When he walked into a room, they made ghostly moans.

Given the teasing Killin faced, Sackett and Morris were understandably tight-lipped about their own sightings. The officers interviewed surrounding businesses and the previous occupants of the warehouse, but none had reported any strange experiences. William Drucker, the store’s insurance agent, visited later in the day. “There’s no proof of vandalism,” he said, but, unfortunately, “we don’t insure ghosts.”

Al and Susy diverged in their approaches, with Susy wanting to tackle the mystery systematically and Al starting to go off script, but when they compared notes, they came upon a discovery. Al was particularly struck by the profound fear Julio exhibited during the events. He also noticed that the events were heightened when Julio would enter the warehouse, as though the “activity revolves around Julio.” This fit with the patterns Susy was trained to look for. In Recurrent Spontaneous Psychokinesis, or RSPK, parapsychology’s technical category for poltergeists, the disruptive entity was usually considered triggered by a particular individual, often an adolescent or young adult going through emotional turmoil from trauma or transitions, which fed into a general disruptive psychic energy. Julio may have been that trigger.

Susy’s task was to find a link between Julio and the incidents. But once again, Al was impatient. He thought about José Díaz, the father of Julio’s girlfriend, who had come to the warehouse with Maria to visit Julio in the past. José told everyone he was a medium, and Al thought maybe his powers could accelerate their progress.

Susy was not present at the warehouse when José took up Al on an invitation to visit on January 16. José, a hefty, confident man, touched his temples and then “closed his eyes and whirled around.” He “went into a trance state and then said there was a big alligator in there or a small dinosaur (invisible because in spirit) who were throwing things around.” To apply the pseudoword in the company name, if José was right, the traditional poltergeist had undergone a “tropication,” engineered by a gator spirit.

Still anxious to speed up a resolution, Al also brought in a friend and ex-business partner, Howard Brooks, 58, a professional magician who performed at hotel shows. In one of his favorite tricks, Howard would make a watch disappear and reappear on his wrist and ask the audience if they liked the trick. They’d always answer yes—and then he pulled back his sleeve to show watches all the way up his arm, joking, “Great! I can do it 10 more times!”

To deceive others during his performance, Howard had to know how the mind worked. The irony of his profession was that he’d become deeply skeptical over time. He learned that its secrets tend to disappear when watching the world closely.

Howard laughed when Al told him he thought a ghost was in the warehouse. “What kind of gullible fool are you? You obviously have an employee who is playing tricks. Just a little piece of string and some spirit gum will do it easily. Or some dry ice. Any magician can do [it].”

Howard agreed to examine the place. Officer David Sackett was returning to the warehouse at the same time. Before Sackett, 34, joined the Miami force, he worked as a private investigator for the famous Pinkerton agency in New York. David had remained intrigued enough by the incidents that he came on his day off, and brought along his wife.

Around noon, Howard, having called his friend Al a “moron” for taking the poltergeist idea seriously, was at one end of an aisle and David and his wife were at the other when two boxes fell from the top shelf. All three saw the boxes fall and land perfectly on top of each other. Howard and David examined the area for trickery: strings, wires, any of the other contraptions that Howard or other magicians might use. They found nothing.

Although Howard still refused to “buy the spook theory,” the magician was forced to admit that “something did move those [boxes], and I couldn’t figure out what.” David and his wife came to the same conclusion. “I don’t see any gimmick or trick to it,” the policeman confirmed.

In a collateral effect of Al’s parade of guests, word spread to the community about what was happening. Outsiders got glimpses of strange happenings. Days earlier, a driver for Rapid Delivery Service was at the back door when glasses fell from a shelf. Other delivery drivers witnessed unexplained events.

With rumors came the risk that Al’s reputation and business could be impacted. He had been a business leader in the area, including as the chairman of the Interclub Relations Committee of North Dade, which planned and sponsored community events. Al decided he had to pivot away from his strategy of keeping things quiet. He needed to go public. While he was at it, Al invited the press to come to Tropication Arts, embracing the showmanship that came with being in the novelty business.

Julio found the warehouse overflowing with new faces. Local and national newspaper, radio, and television reporters flocked to Tropication Arts, including Tomás García Fusté, a refugee who felt a personal connection with Julio, who worked for WFAB, a station focused on the Cuban community in Miami. Fusté could understand Julio’s determination to find a stable life after his family splintered between Cuba and the United States. The warehouse had become a circus with Al as ringmaster. “I’m a very skeptical man,” Al told the Miami News. “I’ve never been able to believe in a religion, but now it’s converting me into something. I don’t know what.” He put the reporter on hold when his bookkeeper rushed in. “I’m back. My bookkeeper tells me a box of burned leather novelties flew off the shelf.”

Al had to tape newspapers across the large front windows to hide his employees from gawkers. He pulled down the iron grate at the back of the warehouse.

Some respected members of the community were allowed in. Robert Plaisted, a professor in the Institute of Marine and Atmospheric Science at the University of Miami, and Dr. Jack Kapchan, a psychologist from the University of Miami, observed multiple incidents. Reverend Richard A. Seymour, a Baptist minister, saw a box move on its own on a shelf and noticed two other boxes crash to the ground without explanation. The minister began to pray in the back of the warehouse with several others, even as another box fell. “I don’t think I can do any good right now,” the minister said. “But I will have my congregation pray for you Sunday.”

If puns were any indication, Al and even his curmudgeonly partner Glen lapped up the attention.

“I know I don’t have a ghost of a chance to understand it, but still, I make the effort,” Al said.

“That’s the spirit,” Glen added.

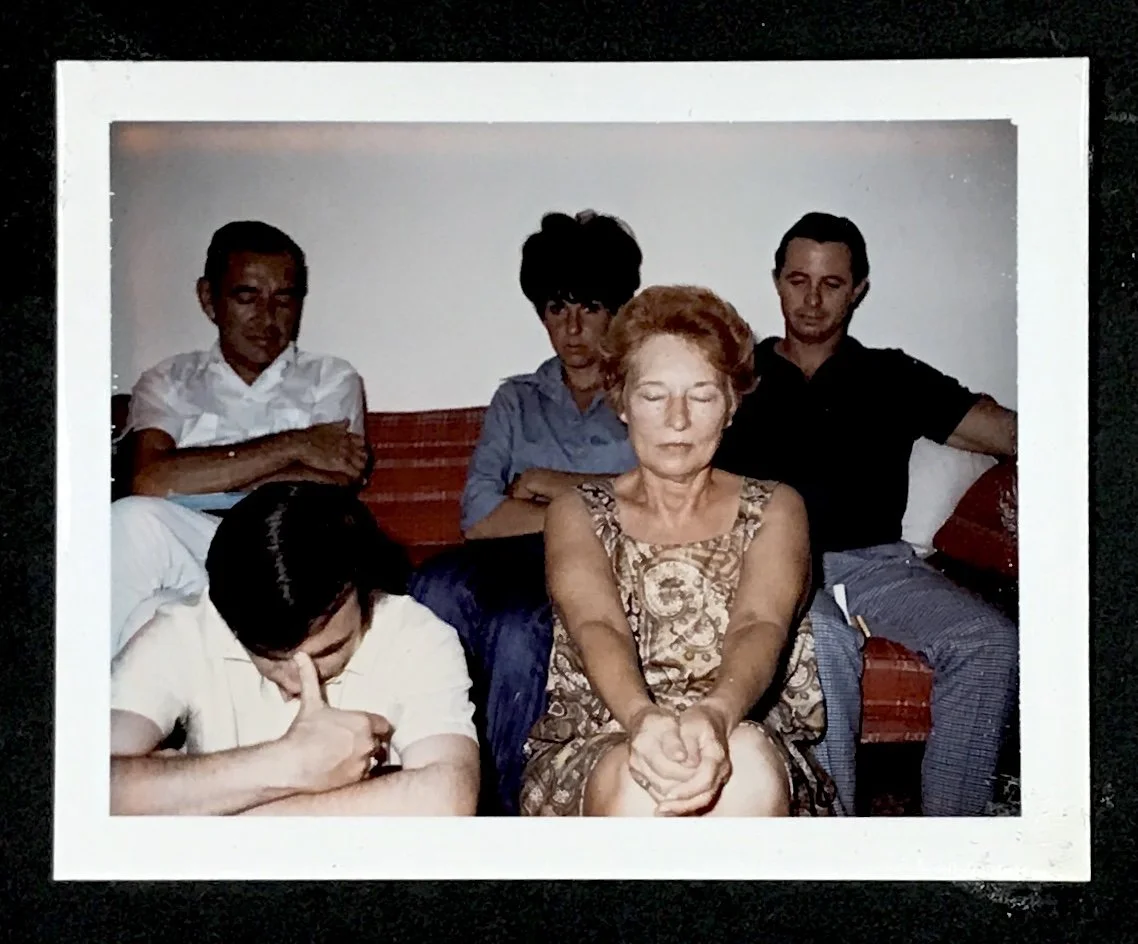

Susy Smith leading meditation group.

With objects falling, swerving and crashing, members of news organizations experienced their own unexplainable moments, including the Cuban reporter Fusté (“I don’t believe in ghosts, but I know what I saw,” he said), two CBS News employees who staked out the warehouse at night (they “did not want to believe [what] had occurred,” but could not explain it), and Dave Haylock, who was assigned to observe Tropication Arts for a European television network. Haylock, a highly experienced cameraman who invented the BetaMarine Underwater Camera System used by Jacques Cousteau, had an encounter that harkened back to the “break out” incident Tropication experienced the previous year. He was getting footage outside of the building in the middle of the night. The warehouse was closed for the night: empty, dark and locked. Haylock reported something that when he was facing away from the store, he heard “raps on the window.” Later, when he explained the sounds, he knocked his knuckles on a desk. Haylock recalled that the sounds stopped whenever he turned to face the store. He later told Al that it sounded like it was “someone inside trying to get out.” At another point, Haylock and a second witness watched a glass tumbler in the air; not falling, exactly, but seeming to spin and float “at an angle.” Haylock snapped a photo of the glass, still “bouncing and quivering” on the ground after falling.

A Miami Herald photo captured a moment with Julio trying to work in the background, looking on with some hesitation, as the stress took its toll.

“I’d quit today, but I need the money,” Julio confided to the reporter. “How do you explain it when you see with your own eyes things jumping off the shelf?”

Susy Smith took Julio’s distress very seriously. On several occasions, she asked permission to put her hand on Julio’s chest after a box dropped or a glass shattered, and his heart was “beating frantically.” His skin paled, covered in sweat, his reactions were dramatic and instantaneous.

The renowned team of Bill Roll and J. Gaither Pratt, pioneers in parapsychology, finally arrived from North Carolina to help investigate. They, too, agreed the phenomena seemed to zero in on Julio. The witnesses, parapsychologists and journalists turned the purported Tropication poltergeist into one of the best-documented, most-widely observed paranormal episodes in American history, and indeed the best-documented, most-widely observed paranormal episode in the history of tropical-themed tchotchkes warehouses.

With all the professional analysis and observation, the theory that struck a chord came close to home from José, Julio’s girlfriend’s father.

Though lacking formal training, José’s seemingly absurd pronouncement of a “big alligator in there or a small dinosaur invisible because in spirit,” tapped into a deep vein of Julio’s cultural heritage, which the two shared. Cuban tradition featured a supernatural figure called the Madre de Aguas, or the “mother of waters,” a paranormal reptile, snake or serpent, who could be corporeal or ethereal depending on the lore, and who in some renditions, searched eternally through water for a lost son while seeking retaliation against those who divided the family. The entity was considered almost invincible, including being impenetrable to bullets in its physical form and in variations, could emit flames.

In light of the mythology, it was impossible not to reflect on the influence on Julio of his mother still being across the ocean in Cuba. Versions of the tales of Madre de Aguas included trapping people into dream states and, at times, being carried away by the dreams toward the water–an eerie reminder of Julio waking up from nightmares and finding himself compelled to amble through Miami to Biscayne Bay. The creature’s fiery characteristics evoked the smell of smoke in the warehouse at the very start of the incidents.

For believers in the idea that the Tropication haunting was particularly encircling or linking itself to Julio, the spirit’s actions could range from mischievous to threatening but could also seem protective. In fact, the unexplained events began after Glen Lewis came down too hard on Julio with his new staff policies and angered the restless young man. Later, Glen was skeptical of the incidents, micromanaging the staff, until the purported poltergeist ramped up to the point where he had no choice but to acknowledge “something was mysterious about the whole thing,” and stopped pestering Julio.

By studying the accounts and legends of Madre de Aguas, the experts could try to trace the nature of the phenomena before its power increased.

Julio’s dreams intensified, as did the trance-like states that followed when he woke up from them. When not walking as though hypnotized to the water’s edge, he found himself ambling blocks from his house to the train tracks, in the darkness, sometimes in the rain.

The Madre de Aguas is said to sometimes appear in reptilian form, but at other times she is said to appear as an enchanting woman, often riding alligators or crocodiles, looking for youth to escort through dangerous waters–ravines, seas, rain storms. Her feet are turned backward, and she walks with a peculiar gait. When she leaves footprints in the mud, they are facing the opposite way than she traveled, eluding those who try to hunt her down.

When others found out about Julio’s nighttime wanderings, they would urge him to be careful, but Julio couldn’t quite articulate the feeling that overtook him. “I’m not afraid of dying,” was the best he could explain, which also fit the centuries-old stories of Madre de Aguas throughout Latin America.

Madre de Aguas leads her targets long distances. In her human form, she captivates young men, though her reptilian form is still visible in her glowing green eyes. For those who looked closely at the figure, her musculature is powerful, statuesque, the form of a warrior, but most witnesses fail to see anything but her beauty. As they face her, men feel drowsy and numb. They are in her thrall.

Walking along the train tracks, where Julio would find himself, was particularly perilous. In Miami, passenger trains were infrequent but industrial and cargo trains charged through the city at night. The rain made the low visibility worse, particularly in those heavy South Florida thunderstorms, which could escalate without warning. Julio kept walking as though he could not stop if he wanted to.

The longer her targets follow her, the more they are consumed by a fever and madness that they struggle to break out of. Her human form can crumble, revealing the monstrous reptile or serpent, and her unluckiest targets lose their balance and control over themselves, falling to their deaths, or getting caught in storms, floods or currents.

At one point along Miami’s crisscrossing tracks, at the Eureka Drive crossing at 150th Avenue, a diesel engine was pulling a single caboose. One of the dangers as Julio walked through the night were the cars and trucks that did not see or pay attention to the tracks, or tried to take shortcuts over the tracks. A green bus had picked up a group of tired Puerto Rican immigrants, who had been clearing away damaged poles all day. The bus drove too close to the tracks, and in the rain, the train’s engineer only saw the vehicle at the last moment, blowing his whistle and throwing the brakes on. But it was too late. The train cut right into the bus, the brakeman helplessly looking back at the tracks and exclaiming, “Good Lord, we’ve killed a bunch of people!” 18 were killed, 16 wounded, in the worst traffic-related accident in the county’s history.

The Madre de Aguas in her journeys is sometimes said to seek a place to die and, presumably, give way to a new incarnation of the spirit who will look for new targets. As her search for a place of her demise continues, more destruction would follow in her wake.

In his accounts of his experiences in the aftermath of his dreams, Julio could not give many details of what he saw. Memories seemed blurry, even from hours before, and he craved a way to find normalcy and stability.

At the warehouse, seemingly playful incidents gave way to more frightening ones. One visitor, nearly smacked by a falling ashtray, was overwhelmed by a peculiar feeling, that seemed, in her words, “to be both inside and outside, as if the air is so thick you could almost cut it.” Ruth May, the company’s novelty artist, reported a mug hitting a shelf with such force that it could be heard across the warehouse, risking the heavy shelving collapsing onto her. Shards of shattered glass from various objects often flew through the air. At one point during the events, a framed picture crashed down on a visitor’s hand. With the objects that were reportedly flying around the warehouse, forklifts and ladders used for stocking purposes were a moment away from being triggered or knocked over, becoming hazards that put the employees’ lives at risk.

For believers, the pattern of Madre de Aguas became clearer–the spirit attached itself to lost young men with broken families, shielding them at their most vulnerable, but also generating chaos and disruption around them, unless her subjects found a way to regain control over their lives.

José had to ad lib the next steps. Referring to his earlier statement about an alligator spirit in the warehouse, he clarified that an “evil spirit was showing itself to him in this form.” José was convinced that spirit was reacting to Julio. Julio was a “potential medium,” and he needed to develop his power “for his own protection.” When Julio accepted his destiny and believed in himself, José thought Julio could drive away or control unwanted spirits.

José instructed Julio to take a milk bath, an act of cleansing, in which Julio spoke prayers and incantations. Julio reported to Susy that he was “very frightened” during the process, and may have caught a cold from it. José also brought Julio along to several psychic sessions. At one point, Julio went into a trance, and at another “a key suspended in a drinking glass” was observed “hit[ting] the sides of the glass” by an apparent mental energy.

On the night of January 24, when the employees had left the warehouse, Al allowed José to conduct an exorcism ceremony. In the dark space, José created a makeshift altar, with a rubber alligator to symbolize the spirit’s transient form. He littered the shelves with palm fronds and cactus leaves and arranged toys and items at other locations in the warehouse. “Look,” he told the spirit, “these are for you to play with. Leave everything else alone.”

When a beer glass shattered amid his exorcism, José paused, bracing himself to complete his rituals.

Everyone was curious how the exorcism might change the fate of the warehouse, but none could foresee the twist still to come. When the Tropication team arrived to work, police cars flanked the building. In itself, this did not seem cause for alarm. The police had made regular appearances at and around the warehouse during the previous weeks, and officers made up some of the witnesses to the phenomena.

This was different. There had been a burglary overnight. The back door had been forced open. Al’s movie camera, a typewriter, costume jewelry, and petty cash were missing.

Al called the police, who arrived around noon. Sergeant James Haddad, the detective, was curt. “I’m not here to learn about ghosts,” he told them. “I’m here to see about a robbery.”

When Julio reported to work, he was brought to the station for questioning. Despite his protestation to the contrary, Haddad was not only looking to wrap up the robbery call, but to solve the enigma of the warehouse that had captivated South Florida. A young immigrant was the ideal fall guy. The Cuban population in Miami had been increasing in leaps and bounds in the last several years since the Cuban Revolution, and blaming Julio played into a larger backlash that viewed the community as intruders. Haddad accused Julio of having been behind the alleged poltergeist all along.

Susy reported that the police leaned into Julio’s identity as a refugee, berating the 19-year-old “with the false suggestion that his mother had been left in Cuba deliberately because she was an unworthy person.” Julio wept when recounting the events.

“Police Tell How Youth Was ‘Ghost’” read the headline in Miami Herald. The story noted about Julio: “His trick was simple. Slender threads placed at strategic places toppled boxes and glasses from shelves.” Sergeant Haddad claimed that not only did Julio confess all of this, but that he had failed a polygraph test. Haddad announced “the case is closed,” but continued his assault in the press, calling Julio “a sick boy who wants attention and to get it he became the ‘ghost.’”

Julio had almost certainly committed the robbery. A key had been used to open the cabinet holding the typewriter and petty cash, which pointed to an employee, and neighbors observed a small blue car matching Julio’s near the alley and saw two young men carrying a box.

However, Julio adamantly denied having anything to do with the unexplained events. The relationship between the two events–the robbery and the phenomena– appeared to be the opposite of what the detective suggested. Involvement in the robbery did not indicate involvement in choreographing a poltergeist; instead, the stress of the unexplained incidents and the increasing involvement of his girlfriend’s father (which embarrassed him) had pushed Julio, who already had been desperate to quit but lacked the money to do so, to swipe goods from the warehouse so he could leave the job. Dr. Jack Kapchan, the University of Miami psychology professor who came to know Julio, believed “a great deal of his confusion seems to be the result of the strange occurrences around him, and the way he has been treated recently.”

Moreover, with everyone already believing that the phenomena was tied to Julio, his actions had been carefully scrutinized. David Haylock, the photographer, kept a close eye on Julio during his hours at the warehouse, but saw the young shipping clerk do nothing incriminating. Haylock explained: “I was seriously trying to catch Julio at it, but several things occurred when he was nowhere close enough to the activity to have been able to cause it in any normal way—with his hands or strings or wires or a stick or anything else. Also I watched him when he did not know it, and I never saw him do anything suspicious. I can state that although I think the activity was somehow associated with Julio, through the power of his mind or in some other inexplicable way, the boy was not doing it by any physical means.” Susy, who had been a fixture at the warehouse, had also never seen Julio do anything notable. No strings or threads were ever found attached to any of the objects that moved.

Julio was also adamant that he never confessed to Sergeant Haddad to being part of any hoax. “I never said I was the ghost,” Julio insisted to a reporter at the Miami Herald.

The detective returned to Tropication Arts for a victory lap. There, Sergeant Haddad sat down with Julio and Al. It was an intimidating confrontation for the 19-year-old, staring down a veteran police investigator. But Julio remained steadfast. He reiterated that he confessed to nothing, and that the detective himself had lied.

The detective “did not deny it,” Al later said in astonishment. “He just got red in the face.” The detective was not used to having the tables turned on him. Evidence suggested the detective had seen an opportunity to step into the spotlight that had been shining on the Tropication by insisting he had solved the mystery. Haddad, suddenly self-conscious and humiliated by Julio’s allegation, seemed speechless, even powerless. Haddad faced the bizarre, almost-dreamlike sights of the warehouse–the traveling paranormalist Susy Smith wielding her cane like a sorceress’ scepter, an employee holding a rubber dagger, Iris stamping objects with a rubber rectangle reading FLORIDA in a hypnotic rhythm, Howard the visiting magician with a row of watches running up one arm and a showgirl he brought along on his other, an alligator head ashtray seeming to glare at him with shining hypnotic yellow eyes. And something strange in the atmosphere, something that seemed to make him lose his usual facade of composure.

When Sergeant Haddad scrambled out of the warehouse, his life would never be the same. Soon after, unexpected evidence materialized that the detective had made a deal with what the Miami Herald had called “the most arrested criminal in Miami history” to look the other way in allowing serious criminal enterprises. Haddad was indicted several months later on bribery and prostitution charges. During the investigation, an assistant public defender said Sergeant Haddad was “known to lie.”

Julio asked that the magical “symbols” placed around the warehouse by José, which had seemed to calm the unknown force, remain in place. The young man had reason to feel more at peace than he had in a long time. The police detective’s fall from grace backed up Julio’s assertion that he was not involved in any hoax, as did a lack of evidence that there had ever been a confession or polygraph test as Haddad had claimed. Unlike Julio’s own father, who had drifted away from him in favor of a new wife, José and Al had stood by him during the crisis with police, as had Julio’s dysfunctional found family at the warehouse.

In addition, Duke parapsychology director Bill Roll was so intrigued by his observations of Julio in Miami, that the Psychical Research Foundation requested that Julio travel to Durham, North Carolina, on an all-expenses-paid trip for two weeks, to test and study him. Susy convinced Julio the trip was worthwhile and drove him to the Miami airport for departure.

Roll wanted to assess Julio’s performance on psychokinetic (the power of mind to affect a given setting) tests. One of these tests involved a rotating dice machine. An operator turned on a switch, and then two dice dropped down a container, hitting baffles during their drop. On the second trial, Roll reported that “the end of the container fell out,” that is, spontaneously broke open, “and the two dice tumbled to the table.” This had never happened before at the Duke laboratory but happened again several more times with Julio. In general, Julio scored markedly higher than average on the lab’s tests, the chances of which being coincidental were put at “more than 100-to-1” by Roll.

At another point, while a depleted Julio sat down to try to recover his strength, a vase in the adjoining hallway fell down and smashed. Several institute researchers were watching Julio at the time, and he had been closely accompanied and observed by others the entire afternoon, eliminating the possibility of manipulating the vase in some way. Roll was impressed: “As far as I know, there have been no other apparently genuine poltergeist incidents in a parapsychology laboratory.”

Returning to Miami, Julio’s absence from Maria had made both feel all the more certain they belonged together, and within a couple of years they would marry and have a child. While confronting what had occurred at the warehouse, Julio had gained enough confidence to move on from Tropication Arts while feeling he and Maria could establish financial security together. Tropication Arts remained in business through the late 1970s.

Julio continued to grapple with unresolved feelings of anger and resentment, and with new jobs came more unexplained incidents, particularly at times when Julio felt unreasonable demands or verbal abuses directed at him, or when he gave into feelings of frustration. He got into trouble with the law at various points. At one point, Julio was robbed and shot multiple times, including a bullet that shattered his aorta, defying all odds when he survived after being given last rites by a priest. He would later reflect, somewhat opaquely, on the experiences of his early adulthood: “I liberated myself from the chains that in the past controlled my mind and tied me to evil things. I got a good source of power, and I am using it now in a constructive way.”

Before Julio left his position at Tropication Arts, there were days in which all was quiet in the warehouse. As Julio looked around, something seemed off about the peace.

The other employees and Susy Smith agreed and realized what it was. Against all logic, they missed the mischievous force the way they had once missed the wildness of Al’s pet monkey. Bea, the artist who originally called the radio station, asked Curt to clear away the talismans left by José Diaz. He did, and an ashtray soon crashed to the ground. “We all cheered,” Susy reported, including Julio, who wore a big grin.

“I feel happy,” Julio would later say. “[It] makes me feel happy; I don’t know why.”