WHEN ethical crusaders spread a rumor about a grizzly murder captured on film and distributed for entertainment, a down-on-his-luck producer spots a chance to make a killing.

The belief that people were being murdered on film for profit and private amusement spread across the U.S. like wildfire. Behind it was an outraged accountant named Raymond Gauer.

Gauer was dumbfounded and disgusted by the speed of America’s decline into “moral anarchy.”

Back in the late 1950s, when he went to the police to report that a business that had recently opened near his Hollywood home was selling dirty magazines and marital aids in broad daylight—near a popular kids’ date spot, no less—the cops raided the shop within days. When he started driving around LA hunting for more sex shops to shutter, local authorities heeded his tips and applauded his work. And when he joined Citizens for Decent Literature, a national anti-smut advocacy group, to organize boycotts against prurient businesses and letter writing campaigns urging lawmakers to pass stricter anti-obscenity laws, thousands of citizens, dozens of legislators and even a few governors flocked to the side of the 53-year-old Christian family man-turned-moral crusader.

They all accepted the simple, self-evident truths he shared in newsletters and a stump speech he delivered to community groups: Sex is great, and there’s nothing wrong with a little blue humor. But porn is poison. Young men who consume it are drawn slowly but inexorably into crime, perversion, and even sodomy. The unchecked spread of smut was clearly responsible for the wave of violent crime ravaging the nation, and the waning strength of Christian morality.

Even if he couldn’t eradicate porn wholesale, throughout the 60s Gauer took it upon himself to at least push it back into the margins, where it would pose no threat to good, upstanding folk. He scored a position on LA County’s Commission against Indecent Literature that allowed him to guide the flow of local censorship laws. And as one of the CDL’s most prolific lobbyists, he liked to brag that he’d played a major role in toppling the career of Abe Fortas, one of the most outspoken proponents of unrestricted free speech on the Supreme Court. Or about how he'd helped to bury a report authored by a presidential commission that concluded that porn wasn’t actually all that harmful.

He was especially proud of a letter of commendation he’d received from that exemplar of justice and morality, J. Edgar Hoover—which further noted that Gauer ought to check out a book that detailed a clear conspiracy between pornographers and communists to use smut to “demoralize the young of [the] country.”

Then, suddenly, at the turn of the decade, justice turned against common sense morality—against him. The courts kept making it easier for people to make, sell and own porn without restrictions. The public seemingly started buying into egghead arguments that the so-called data didn’t actually support a connection between porn and violent depravity. An upstart district attorney even had the gall to sack the CDL’s key ally in LA’s justice system for incompetence, calling the rigor of the group’s reporting and the veracity of its claims into doubt in the process. The DA not only kneecapped the CDL’s political power, he also cost Gauer his prestigious Commission seat.

Gauer railed and raged. “Things are rotten in Denmark,” he sneered in a press statement aimed at the American Publishers and Distributors Association when it refused to take a hard stance against hardcore content. “And you are trying to make them even more putrid here.”

But he increasingly began to feel as if no one with power wanted to listen anymore. By 1974, he saw explicit magazines for sale in barber shops and liquor stores across LA. He saw small theaters giving up on wholesome films in favor of the filthy lucre that came with showing hardcore sex on screen. He saw what he perceived as the literal, orgiastic end of Christian decency—of America itself—barreling toward him.

So, as he sat down to write his column for the fall edition of the CDL’s National Decency Reporter, he decided he’d have to wake America up to the ultimate horror of pornography. Or at least his hundreds of thousands of subscribers, including many clergy members and cops—the faithful (and vocal) few who still embraced him as both an issue expert and moral authority.

“Competition forces the pornographer to constantly seek ever more perverse material in order to keep customers coming back,” he wrote in a front-page article entitled “Perversion for Profit.”

“The result is that much current pornography is literally indescribable… Reliable informants report as many as 25 ‘snuff films’ in circulation among certain pornophiles. These incredible films culminate in the actual murder of human beings during a sex orgy—thus providing the ultimate ‘kick’ for sick porno voyeurs.”

He concluded with a question: “Can it get any worse?”

Gauer's readers latched onto this outlandish, yet to their minds somehow believable, claim and spread it through their communities. Eventually, someone even got Gauer's article onto the desk of United States Attorney General William Saxbe, who asked the FBI to "tell me whether this information is simply an alarmist lie, or if it could be true."

As the news spread across the nation, a 30-something down-on-his-luck softcore porn distributor named Allan Shackleton got a call from a bad B horror movie producer, who said he had a great new idea for how he could make some quick cash.

Allan Shackleton was in the biggest bind of his ill-conceived cinematic career.

Although he had no background in, or even love for, film making or marketing, he'd gone into softcore porn a few years prior because he considered it an easy path to quick cash. Sex sells, and in a puritanical culture, softcore porn was pure gold. But the same tides of titillating change that outraged Gauer had decimated Shackleton’s already dicey business, which focused on buying exceptionally low-end nudie flicks no one else would touch on the cheap, convincing theaters to play them and hopefully profiting.

Following the phenomenal success of pornos like 1973’s Deep Throat, which drew in mainstream viewers and press attention, audiences wanted hardcore films now, not his softcore trash. That was a big problem for Shackleton, who had no stomach for the murky legal waters, and possible obscenity charges, that such blue boundary-pushing films put producers and distributors in. He did ask one softcore director he'd worked with a few times to make him a cheap hardcore film, to test the waters. But watching even that mild fare left him white as a sheet, screaming, "I can't sell this! I'll go to jail!"

So in 1974 Shackleton tried to get out of the porn business by, at the suggestion of an associate, producing a burlesque Star Trek parody called Star Drek. He hired an established screenwriter and tracked down a Trekkie in Pennsylvania who'd built a full-scale replica of the bridge of the USS Enterprise, booking it as a set. But early the next year, his lawyers warned him that Star Trek's rights holders might sue him for the project. So, partway through production, he dropped everything and ran, deep in debt and truly desperate.

That’s when Jack Bravman called, offering Shackleton the distribution rights to a film called Slaughter.

The movie, by any cinematic evaluation, was a disaster.

Years earlier, a few lawyers had given Bravman $40,000 and told him to go make a B horror movie based on the Manson murders. They didn’t care if it was any good—or even if it showed in any theaters. They just wanted to use the production as a tax write off.

Bravman called a filmmaker he knew, who agreed to direct on the cheap and crapped out a script for him about a guru named Satán who led an all-female biker gang. Satán's crew lured a wealthy European film producer and his blond, pregnant American actress wife into their orbit and eventually murdered them. There was also a ludicrous side plot about Arab arms dealers.

Hoping to earn a hefty "salary" while sticking to his miniscule budget, Bravman decided they should shoot in Argentina to cut costs. He convinced a regional airline to give them free tickets in exchange for featuring one of the planes in an American movie. He didn’t want to pay for a cameraman, so he just had the director's wife shoot everything—despite her lack of experience. He didn't want to pay for sets, so they used a desk in an open field as a police station. They didn’t want to bother with sound equipment, so they filmed silent and decided to dub in dialogue later. After just four weeks, they wrapped production and flew back to the United States.

No one would touch Slaughter. Not because it dealt with the Manson murders—plenty of films already had—but because it was sloppy, incoherent, and boring. Fortuitously, a completely unrelated filmmaker was working on a movie called The Slaughter. Concerned that Bravman might eventually find a distributor and audiences would mistake the two productions, he offered $10,000 for the rights to the movie’s title to avoid confusion. Bravman had lost the lawyers’ money, but they still got their tax write off and he got a $10,000 cherry on top. So he decided to throw the reel into a storage bin and forget about it.

But in a mixup, he'd recently sent it to a porn theater owner in the Midwest, in place of a softcore film he was distributing.

“What’s the matter with you?” the irate theater owner screamed at him over the phone. “What are you sending me, a snuff movie or something?”

It was a lightbulb moment. Bravman had heard some chatter about snuff films, but he didn't give it much credence. However this guy was naïve enough about even cheap horror movie special effects to think Bravman’s film might depict a real death. Bravman thought he might be able to turn that misunderstanding into something profitable. But he figured he could only sell the idea to a desperate, reckless distributor. Fortunately, he'd met Shackleton a few years back. He knew exactly the kind of man he was, and had a sense of his desperation for some big gamble win.

Bravman sold Shackleton a plan to sell Slaughter to theaters as a real snuff movie then rake in cash on the controversy to come. Shackleton had also heard a little chatter about snuff films. He hung up the phone and cut Bravman a check for $1,500 for the rights to Slaughter.

Fired up by his crude huckster entrepreneurial spirit, and sheer frantic greed, he saw his chance to make a killing. Or at least a very profitable fake killing.

He had templates to follow, after all. Shackleton knew that in '64 a softcore filmmaker had turned a $24,500 cheapo horror film into millions in profits by claiming that it showed the "slaughter and mutilation of nubile young girls." No one believed him, but incredulity filled seats. Shackleton didn't think the half-assed stabbings and shootings in Slaughter lined up with people's beliefs about snuff films, though. So, he took a cue from sensationalist quasi-documentaries playing in Times Square at the time, which featured real footage of indigenous communities intercut with staged scenes of death and cannibalism, and decided to film a new ending for Slaughter. It'd be supposedly surreptitious "behind-the-scenes footage" showing the film's director going into a sexual frenzy after the final shot, and murdering the lead actress as the crew dutifully watched on.

Shackleton was sure this was it: The trash that would make him rich. He had no idea how much trouble he was about to stir up.

The kids, 8 and 10, couldn’t stop laughing. They were visiting their dad for the weekend, and as per usual had free run of his loft, which Shackleton had rented out to film his new ending. The scene was as gross and absurd as anything they'd ever seen. The prop master let one of them hold an eyeball plucked from a sheep's carcass, which he was harvesting for fake gore. The other gawked at the animal guts, strewn over the hardwood floors behind the cameras.

Between the spring and summer of '75, Shackleton had pumped out a sketchy script for his coda: The "director" of Slaughter would call a cut at the end of the film, then tell the lead actress that the violence of the finale had him all worked up. He'd make an advance in front of the crew, but when she rebuffed him he'd brandish a knife, go into a psychotic frenzy, and lunge at her. The crew would stand by impassively as he then pulled a pair of gardening shears out of nowhere. That's where the sheep's guts, plastic fingers, and fake blood would come in.

But beyond that, and renting out the loft for a day, Shackleton had nothing to do with the production. That was characteristic. He never cared about any film he was involved in, so long as he had something at the end of the day to pawn off on theater owners. Instead, he tapped a notorious shlock horror director who'd worked with him on promos for some of his softcore flicks, and who'd gotten him into jogging and other '70s health fads, to handle the production.

Shackleton only gave the director a $10,000 budget. So, while this obscure auteur managed to use a few connections to get one of the special effects guys who'd worked on George Romero's zombie movies, he had to hire random "actors" off the streets.

The coda was scripted to last five minutes on screen, but it took 18 hours to shoot, from 8 a.m. to 2 a.m. And it was a shit show. The loft looked nothing like the original set of Slaughter and none of the actors looked anything like the cast of the original film. Even though they had a SFX pro on their team, thanks to the short timeline and low budget the director's effects were laughable—and riddled with continuity errors. The two kids kept cracking up as the shoot gradually unraveled.

Yet for all the surreal nonsense afoot, 14 hours in, the guy playing Slaughter's murderous director worked himself into such a lather of faux lethal madness that his "victim" had a very real panic attack. Tired and overworked, surrounded by strange people and the smell of a sheep’s carcass, she’d convinced herself that she actually had wandered onto the set of a real snuff film. The real director called a cut, and the loft owner-turned-producer jumped in to talk her down by demonstrating that the knife was a prop, and gesturing to his kids as further proof that this was all a ridiculous act. They took a break to order pizza and decompress, and eventually the actress's nerves faded.

But some of that energy—that genuine fear—crept its way into the final shots.

Ironically, the casting process and the shoot were so bizarre and unprofessional that they spawned rumors across New York that someone actually was out there propositioning young women to make a snuff movie. And that someone had recently imported a snuff film from Argentina, which would be screening soon.

The kissing commenced just as city officials began reciting the prayer with which they usually began their stodgy meetings. Regulars at Philadelphia's City Hall were aghast.

The protesters carried banners and megaphones and held up fists of defiance. But that was all standard counter-culture activist fare by this point. The kissing, though—women kissing women in the hallowed chambers of the nation's first capital—provoked displays of open ire and disgust from the elected officials, most of them older white men.

Moments later, the city’s Civil Disobedience Squad, a brutal police force created in the 1960s to put down protests, pounced into action, dragging these scandalous women out of the Hall's main chamber, beating them, sometimes five-on-one, and brutally pulling them down the marble stairs, some by their hair.

DYKETACTICS! was an anarchist, anti-colonial, anti-racist and anti-capitalist collective of self-identified dykes who'd met at the University of Pennsylvania earlier that year. They named themselves after a queer, erotic short by the feminist filmmaker Barbara Hammer, and were at the vanguard of a new style of confrontational, guerilla activism.

The group’s members lived in a commune setting, shared their finances, and dabbled in nudism, non-monogamy, and feminist art—making paintings using menstrual blood, and the like. But what started as a cloistered collective quickly turned toward bolder public activism, informed by comedic street theater. Their crew pulled stunts like handing out cards to men on the street that read: “You have insulted a woman. This card is chemically treated. In three days, your prick will fall off.” These small performances gradually morphed into hyperlocal political activism, as the group began organizing to put pressure on landlords who wouldn’t make necessary repairs for their low-income tenants, and to protect members of the local queer community against discrimination.

By the end of 1975, the group had decided to take an aggressive stand to protest the slow, procedural death of a local bill that would have enshrined employment, housing and public amenities rights for queer people into Philadelphia law. Their "kiss in" failed to save the bill, and they walked away battered and bruised. Yet the experience left the collective energized—eager to take on more big fights, to keep their cause in the spotlight.

Soon after they were forcibly dragged from the historic white marble and limestone building, they decided to find a way to draw attention to the cops’ brutality. A high profile excessive force case quickly followed.

Although they'd eventually lose that case as well, it drew a ton of attention, sparked conversations and further stoked the fire under collective members like Kathy Hogan, who were increasingly eager to pick higher-profile fights. The group set its sights on local high schools, churches, even a bi-centennial celebration, which they determined discriminated against queer people. But they still drew the line at focusing on local issues and challenging local institutions.

That is until Hogan and a few others caught wind of a local therater's plans to screen a noxious film called Slaughter. In early '76, the DYKETACTICS! crew turned the full force of their creative outrage and anti-misogynistic disdain against the film—and the shameless huckster trying to push it on their community.

The consequences of this protest would be far wider than anything they'd ever done before.

In July 1975, a cub reporter from the New York Post asked Joseph Horman of the NYPD’s Public Morals Squad if he knew anything about snuff movies because he’d heard from a reliable source that one of them had made their way to New York. Should the people be concerned?

Horman didn’t actually care about public morals, or its mission of cracking down on porn and gambling in the city. He had taken a job as a beat cop in 1965 because he didn’t want to work at his father’s pickle factory. Most of his mother’s family were cops and firemen, and they’d told him all his life that the jobs paid a solid salary and led to a good, early retirement. He worked the Times Square beat as a low-level street cop for five years, where he got to know all of the local sex workers and porn shop owners. As long as they didn’t murder, assault or rob anyone, he told them, he’d leave them alone. He thought everyone had the right to do whatever they wanted with their own bodies.

But he was afraid that if he stayed out on this beat too long he’d slowly give in to the culture of brutality the older cops perpetuated. And after he got married, his wife started urging him to transfer to a position with a more reliable and merciful schedule. So he switched gigs in 1970.

Public Morals was a cushy gig. Cops got to drift in casually after nine every morning, and they always had weekends off. They got to go plainclothes, too, so he wouldn’t have to wear the heavy winter jackets they issued to patrolmen in those days.

Horman only took one aspect of Public Morals seriously: Its mission to take down the mob, a force that he and his peers believed had infiltrated every aspect of Times Square, turning mostly harmless sex work into a more dangerous racket for all involved.

In his zeal to bring down the shady actors who made sex work dangerous, Horman grew far too credulous of rumors he heard on the street that conformed with his preconceptions about the perils of organized crime. He was so willing to buy into any story that might connect to some wider, sinister criminal enterprise that pimps started telling him tall tales about their competitors to get him to launch crackdowns that’d open up new territory for them. The gambit often worked.

So, while most cops would have brushed off this reporter’s question, Horman took it as a major tipoff—a dire warning about a new organized criminal evil invading his city through the porn world. He quickly launched an investigation and started rounding up loops, 8 mm porn reels that ran on repeat in the back of sex shops, which depicted scenes of staged brutality within their BDSM tableaus.

Incredibly, Horman’s team approached the loft owner-slash-producer who'd helped shoot Shackleton's coda to The Slaughter to analyze the film. They'd busted him for making porn in the past and knew he had photo science chops. They didn't know—and never would realize—that he was actually part of the shadowy group of snuff makers they were chasing

“These are all laughably amateurish,” the loft owner said. “There’s no way anybody could believe they’re real.” They'd probably come from a Danish fetish studio that got a little overzealous with special effects, he added. The Danes were lightyears ahead of American pornographers in that sort of thing.

But Horman wasn’t convinced. He smelled a possible organized criminal conspiracy. So he kept digging. He needed something to dig into. His wife had left him a little over a year prior, and he was adrift. This big, splashy investigation made him feel not just anchored, but important. “His ego got so big that even I didn’t recognize him,” says Nick “Pickle Fritz” Horman, Sr., Joseph’s brother who runs the family Pickle Works to this day.

In August, New York hosted a conference for vice cops from around the country. The head of the New Orleans Vice Crimes Section came back full of tales about “snuffers” circulating throughout the country. He reached out to a local district attorney, who reached out to the FBI, asking if they had any information about these terrible little films that he could feed to judges in order to get some warrants to crack down on local porn dealers. He stressed that doing so might just save women’s lives.

The FBI dutifully reopened the investigation it had closed earlier that year, after speaking to the moral crusader Raymond Gauer and deciding there was nothing to his talk of an epidemic of snuff than a thinly-veiled attempt to rile up his base. Agents asked around, and realized that rumors of snuffers were suddenly rampant among cops in Atlanta, Chicago and Miami. When FBI officials called Horman, he told them he’d spoken to an editor at the Hollywood Reporter who confirmed that someone in the porn industry wrote a script for a snuff film earlier that year and hired people to shoot it. He added that he was this close to tracking down a copy of the now-infamous Argentine film, which was supposedly sitting in a store in Miami. He had no clue that, once again, he was dancing right on the edge of uncovering Shackleton's scheme. The huckster owned a small theater in Florida, where he was storing early cuts of Slaughter at the time.

Worked up by his own rhetoric, and eager to keep the ball rolling, Horman called the Post reporter back and gave him a smoking gun quote. On October 2, 1975, just weeks before Shackleton started promoting his movie, the Post ran a story titled: “‘Snuff’ Porn—The Actress Is Actually Murdered.”

“I am quite convinced that these films exist and that a person is actually murdered,” the article quoted Horman as saying. He added that, sure, some snuff films just featured simulated murders. But that didn’t mean that there weren’t already dozens of real snuff films in America.

“The most popular film in the country is Jaws—that’s the story of a fish that eats people,” Horman told the Post. “People like violence. Snuff films had to happen sooner or later.”

Four days later, the Associated Press circulated a story about Buenos Aires cops discovering the mutilated corpses of three prostitutes. Tabloids drew an immediate connection to the snuff films Horman insisted were coming up from Argentina and likely screening somewhere stateside.

For the next few weeks, Horman became the go-to source for local reporters running their own stories about the films. In doing so he offered credulous quote after credulous quote. He’d convinced himself that he’d uncovered a true and imminent evil. And he was the hard-nosed New York cop who’d root it out.

Shackleton sat back and watched the news cycle prime the nation for his film. The old-school '20s, '30s, and '40s hucksters he'd based his trash-into-gold business model upon had to put real work—and money—into stirring up a proper panic to fuel interest in their drek. Kroger Babb, the most notorious of the lot, reportedly pioneered direct mail advertising, hired people to inveigh against his movies on street corners, and manufactured fake protests in front of theaters screening his films just to get a modicum of the moral outrage and attendant morbid fascination that Shackleton had stumbled into for free. Buoyed by this win, Shackleton even let a few of his associates believe that he’d planted stories about someone making real murder flicks in New York in the press himself. It never hurts to let your colleagues think you’re a marketing genius.

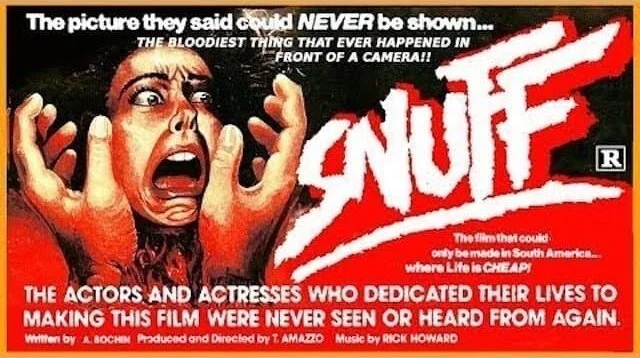

Then, on November 10, 1975, Shackleton kicked his plan into its next phase, releasing ads for the film he'd decided to call Snuff in trade magazines. These promos leaned into Horman’s narrative about his own film. “The ultimate in violence,” an ad in Box Office read. A “Buenos Aires porno import,” another in Variety proclaimed.

In mid-December, an ad spot on WIBC radio in Indianapolis announced that one of their local theaters would host the film’s January premier.

Posters soon went up in Indianapolis. The film that could only be made in South America, where Life is CHEAP! one blared in bolded font.

The Bloodiest thing that ever happened in front of a camera.

The picture they said could NEVER be shown…

The ads were clever. But that was an accident rather than an act of brilliance—a byproduct of Shackleton covering his ass against any potential legal risks. They never claimed the film was hardcore, or that it showed actual murder, but their silhouettes of a nude woman and salacious copy sure implied both. And the ambiguity was tantalizing. They also didn't list any actors or a director, which left the press with no one to talk to about the film save Shackleton himself.

In interviews, Shackleton adopted a smarmy-coy persona, insisting that he was contractually obligated not to answer questions about the nature of the movie’s deaths. However, he said they were too brutal to watch, and that he was only distributing them for the money.

“The movie makers must have gone to tabloid correspondence school,” a New York Times story on the brouhaha that quickly cropped up around the film’s imminent release wryly noted.

In fact, most reporters were skeptical about the film. “Barbarism—Or just Fraud?” a headline in a local Indianapolis newspaper mused. The article lamented that their city had become “the guinea pig in one of the most cynical test-marketing projects ever conceived” by a low-rate flim flam man.

Persona-building puffery about his marketing mastery aside, Shackleton slipped up several times in press statements. Notably, he told reporters he’d initially thought about editing the film for an R rating to expand its audience, but that he embraced a self-imposed X-rating to make it seem more extreme.

Yet doubts lingered in the zeitgeist—in part because the movie just seemed so cheap. The DIY elements of Shackleton's ads made death and depravity feel far more plausible than a big Hollywood rollout would have. He’d set ticket prices at $7.50 each, an astronomical jump over his usual $1 to $2 porno entry fees that made it feel like something especially taboo. And he even stripped the film’s credits, so it now cut from his coda to a black screen and dead silence. The effect was eerie, but also convenient for Shackleton, who didn’t want to pay any of the original cast and crew for their work.

Then, days before his big premiere, the authorities put just a bit of pressure on Shackleton.

And he instantly wilted.

The FBI had actually tried calling him on December 9, but he wasn’t in his office at the time. Instead, they decided to send two undercover agents and a doctor from a Veterans Administration hospital to the Indianapolis premiere to assess the need for potential further legal actions.

But in mid-January, an Indiana prosecutor confiscated the local theater’s copy of Snuff for analysis, forcing Shackleton to bump back his premiere. Two papers banned ads for the movie, on the off chance it was a legitimate recording of a murder, sending Shackleton into a panicked fit.

The prosecutor quickly determined that the film was entirely fake and unbelievable. However, he told Shackleton that he could only screen it in Indianapolis if he issued public disclaimers reading, in full: “This is a theatrical production. No-one was harmed in this production.” (He also decided that he’d still send some cops, just to make sure Shackleton didn’t screen another movie at the premiere that actually did feature real deaths.)

His smug persona obliterated, Shackleton called the prosecutor, begging for a reprieve and insisting that no one would believe the deaths were real, and that putting a disclaimer on the film would ruin him. But the prosecutor didn’t budge. Shackleton folded, utterly defeated.

On the evening of January 16, 1976, Shackleton and a writer he’d hired to help him promote the film paced back and forth in the lobby of the sketchy theater they’d selected for their premiere, muttering to themselves about what they’d done wrong. Why wasn't this working? They’d only counted 16 people in attendance. Unbeknownst to them, at least five were undercover officials and one was a skeptical film critic. Only 18 people showed up for the next screening, and 14 for the day's final run.

The FBI agents in attendance were not impressed. In a six page memo, they declared the film a clear fake, an assessment they dutifully defended in elaborate detail: When the “director” cut off his "victim’s" hand, there was no arterial blood spurt. The heart he pulled out of her chest—far too easily—was too small for a human. She remained conscious for quite a while afterwards. Oh, and that blood was clearly just Karo syrup dyed red.

“It appears as though [Shackleton] would welcome judicial action as a vehicle for publicizing captioned film and, reportedly, he is disappointed that the matter attracted a minimum amount of publicity in Indianapolis,” one of the agents wrote in a report filed on January 22. As such, he recommended closing the case and letting Shackleton burn himself out.

Higher ups decided to keep the case open in the name of due diligence. But when two more agents who attended Snuff’s New York premiere the next month reported seeing the same clearly fake gore, the FBI officially closed the book on its investigations into snuff films.

Indianapolis was a disaster for Shackleton. The film closed after a week. But he was in too deep at this point and felt he had to keep trying. He lowered prices to $4.50 and hired barkers to grab people on the street and drag them toward the theater. He prayed authorities in each subsequent city he rolled through wouldn’t make him include a disclaimer in his ads and before the movie.

Attendance did pick up a bit in the next few towns, but the movie wasn’t the hit he’d hoped for.

Not, that is, until he took it to Philadelphia.

The DYKETACTICS! crew learned in late January that Snuff would premiere in their backyard on February 4.

Hogan didn’t think for a second that it was a real snuff film. She and her compatriots just thought it was clear misogynistic bullshit.

Granted, it was hardly the first film depicting the abuse of women for cheap thrills, or the only one in theaters around that time. And the group had never mobilized against a movie before. They weren't anti-first amendment fascists, after all, Hogan stressed.

But they found Snuff especially noxious because the movie didn’t just feature violence against women. The movie was violence against women. Its framing and marketing also implicitly argued that it’s okay to capitalize on gendered violence. That it’s fine for people to go to the theaters for the sole and explicit purpose of watching a woman get brutalized. That the impulse to satiate their morbid curiosity could easily trump the concepts of female life and dignity.

They could not let this movie premier in their neighborhood.

The crew called the National Organization for Women to see if they’d planned any actions against the film that their crew could join. But a NOW representative politely told them that the organization would never protest movies because filmmakers have first amendment rights, no matter how odious their views, or how brutal and intolerable their depictions of violence towards women.

DYKETACTICS! called a community meeting to discuss the movie. After a few hours of deliberation, they decided they needed to shut it down, first amendment rights or no—and that it was reasonable to cause property damage to convince the theater to pull the film immediately.

They wouldn’t do anything that could harm people, they vowed. But they’d clog toilets, destroy screens and projectors, and do time for their vandalism if they needed to. This was worth it. They started organizing a bail fund for anyone who might get arrested in the protest right away.

But before they put their plans into motion, DYKETACTICS! figured they ought to do Shackleton the courtesy of telling him what they were planning, and ask him to back off of his own accord before they did any real damage. So the day before the premiere they called the publicly-listed number for Shackleton’s New York office.

He picked up.

“We want to talk to you about your movie premiering in our local theater,” Hogan told him. “We’re going to do a demonstration tomorrow. We’re not having this movie in our community.”

“Yeah?” Shackleton retorted with an audible sneer. “Well, bring it on. Pickets bring tickets.”

He laughed and repeated that old, established huckster showman mantra a few more times.

He was derisive and dismissive, scummy and noxious. He clearly had no intention of listening to them, and thought that this was all a big joke. Hogan felt like she was talking to P.T. Barnum.

At 10 the next morning, 35 protestors lined up outside the theater. They faced a line of cops, most of whom they knew by name from previous interactions. But only eight DYKETACTICS! protestors planned to actually storm the theater, fuck things up and potentially face arrest.

One woman broke out from the group and started to shimmy up a nearby flag pole, screaming about how they were going to close down the theater. The cops flocked to her—just as the protestors had planned.

Like a well-coordinated football play, the core eight ran through the gap they left in the cops' ranks and burst into the theater doors. Taggers managed to spray paint a few chairs. But Hogan’s team, carrying jars of honey to dump into the projector, found the booth doors locked. Before she could break down the doors, and before the taggers could reach the screen, the cops swarmed the theater, chasing women through the aisles and dragging them out one-by-one. Hogan remained calm, so much so that the cops let her be for the moment and came back once they’d dealt with the others, hoping to negotiate an end to the disruptive protest with a reasonable woman.

“Yeah, here’s the negotiation,” she said. “You can’t have this movie in this neighborhood.”

That’s when local media showed up. They found a wave of protesters chanting “The Murder of Women Is Not Entertainment,” and waving placards bearing similar messages.

Completely mobbed, the theater canceled that day’s screening. The next morning, after news of the successful protest spread, even more protesters showed up and threatened to further damage the theater. The beleaguered manager gave up and canceled his planned three-week run of Snuff.

The DYKETACTICS! team took the win and moved on to other matters; few of them ever thought about Snuff again. Hogan doesn't even remember speaking to anyone outside of her community about the protest—until recently she believed they were the only group to commit an act of civil disobedience to push back against Shackleton's insidious, sexist bullshit.

DYKETACTICS! protest (Image courtesy of Philadelphia Gay News)

But news of their exploits spread by word of mouth, and through niche feminist papers like Minority Report and The Lesbian Tide. “Many feminists see this movie as a wider conspiracy by both the media and those in authority to ultimately insult and terrorize women,” a columnist for Minority Report wrote, “driving them back to their old subservient and fearful position in society.”

Inspired by coverage of DYKETACTICS!'s apparent success, feminist groups organized similar protests in other cities, starting with New York, which had its own Snuff premiere a little over a week later. A coalition of prominent feminists, including artist and critic Susan Sontag and Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman, pressured New York’s district attorney to open another investigation into the film—which he promptly did. On March 10, he announced at a press conference that his office had obtained photos of the cast eating pizza in the Manhattan loft during the shoot and interviewed the supposed murder victim, and so could (re)confirm the film was a hoax.

For most of the protestors, though, that was beside the point. Over in LA, several small feminist groups coalesced into a super-group called Women Against Violence Against Women to organize simultaneous and sustained protests against 22 theaters from the film’s local March 17 premiere to its inevitable closure—and in front of a hotel Shackleton was staying at around that time.

In their meeting notes, WAVAW members acknowledged that the film was clearly fake. But they also noted that outrage over its supposed contents was a surprisingly potent tool for rallying together disparate groups. So, they decided to play into Shackleton’s claims about the veracity of the deaths in the film in order to galvanize further outrage and activism—using equally dubious and equivocating language.

Allen [sic] Shackleton, the distributor of ‘Snuff,’ is earning his living based on the MURDER of women! they declared in a public statement.

The group also sent a letter to the Argentine embassy on March 12, alerting them that American filmmakers may have murdered an Argentine woman for entertainment and screened the footage for international audiences. They urged Argentine authorities to investigate Shackleton.

WAVAW officially denounced property damage. They even set up a system of protest monitors to make sure everything would stay safe and calm. Just the same, on the night before the LA premiere, women lobbed bricks into several theaters’ windows wrapped in notes that read:

“We will not allow male film pimps to make money selling dismemberment and murder of women. We will not allow women’s blood to be shed in the name of entertainment. We are outraged by this barbarism. Shut down Snuff or we’ll [shut it down] our way.”

As ever more sinister rumors about the film, or its real-life precedents, swirled, anti-Snuff protests grew more extreme. Protesters in DC lobbed bricks and stink bombs into theaters during screenings to harass patrons. In Rochester, New York, they poured glue into door locks to render entrances unopenable and broke windows. In Morris Plains, New Jersey, someone even allegedly hucked a Molotov cocktail into a projector booth during a showing. In Orange County, California, anonymous protestors made bomb threats against theaters and newspapers advertising the film, urging them to stop profiting on violence against women.

A familiar yet wholly unexpected faction also joined in on the action: Starting in LA, and increasingly at subsequent protests, activists noticed not just local feminist colllectives but also evangelical Christian groups, like the ones Gauer whipped into a fury and helped mobilize against the specter of snuff, showing up to protest the film alongside them.

"Strange alliance!?,” a WAVAW member wrote in her notes on their efforts.

Feminist and evangelical groups had just discovered a common cause, which they rally around to this day: anti-porn advocacy.

Both viewed Snuff as a pornographic film, meant to titilate its audience above all else. And both viewed snuff films in general as the real and rampant logical conclusion of porn's competitive evolution into ever rougher and more outlandish territory. Even though he no longer expressed an interest in or got involved with the protests around Snuff, this was Gauer's logic exactly.

DYKETACTICS!, WAVAW, and several other groups that followed their lead believed they’d won their war against Shackleton: They got dozens of theaters to either cancel their runs of Snuff before they’d even started, or to cut them short.

Except they didn’t. In reality they had created a surge of new gray market demand for the film.

The theater manager in Philadelphia, the site of DYKETACTICS!'s catalytic protest, didn’t really cancel his run of Snuff. He just moved it to a theater he operated outside the group's territory. Shackleton actually developed a system for moving Snuff up the road a bit for impromptu screenings to account for protests-based closures, diverting both pre-existing and uporar-born foot traffic that-a-way. As one WAVAW operative noted at the time: “He feels that the demonstrations against the movie have done nothing but promote it, which he thinks is great.”

The hype the protests generated around the film probably did do far more to promote it than any of Shackleton’s half-assed ballyhoo ever could have. In fact, the more earnestly protestors insisted that Snuff may really depict the death of a woman, or at least mimic a real snuff film, the more curious audiences grew—and the more credulous they became of its cheesy violence. A Minneapolis cop who attended a local showing even wrote a report claiming that there was no way Snuff's violence could have been faked. It made him feel physically ill. It had to be real.

Back in New York, that loft owner-slash-co-producer of the film’s faux violent coda went out to dinner in Little Italy in the spring of 1976 and heard a guy at another table telling a date how he’d “seen the film and that woman was definitely killed!”

He nearly choked on his spaghetti.

By April 1976, Snuff was the ninth highest-grossing film in America, behind Blazing Saddles. In a week at one New York theater alone it grossed over $66,000, which would be well over a quarter of a million dollars today.

POSTSCRIPT

When Hogan, still a feminist activist who's deeply enmeshed in local politics, heard about Snuff's success following DYKETACTICS!'s protests, and the role the group may have played in it, she was not fazed. Whatever happened after their action, she says, is really beside the point.

"The point is that, if something happens in your neighborhood, are you going to respond or not?" Of course you are, she says. You must. That's your duty to society.

"We did our best," she adds. “This was an obnoxious, horrible little thing in our neighborhood. I think we did the right thing."

She also still believes that, given the way society treats women, snuff films probably do exist in some deep, dark corner of the world. Although she has spared few thoughts for them since '76.

Horman, the self-important Public Morals police officer, never had his grand heroic moment—or a reckoning with his zealous mistakes, and his ultimate role in fomenting a baseless moral panic. After he'd realized a woman he was dating in '75 had started doing sex work, he had a mental breakdown. He moved to a desk job crunching crime statistics, left the City for Long Island and after the ‘80s tried not to think too much about his time chasing snuff shadows. He died in 2001.

Although Gauer, the moral crusader who started the whole mess, stayed out of the Snuff row, he kept inveighing against the evils of porn into the ‘80s. He died in 1997. His lasting claim to fame, however, was not his anti-obscenity work but a popular Christmas ornament showing Santa kneeling before the baby Jesus, as he thought was right and Christian and proper.

Rather than get involved in Shackelton's scam, either to disrupt it or try to hone in on his profits, Bravman decided to wash his hands of the whole business. He moved to Montreal to make cheap horror movies and eventually moved on to his new life as a Florida realtor. He still gets a good chuckle now and then thinking of the chaos that flowed out of Shackleton's scheme and engulfed him.

Shackleton, always eager to squeeze the last drop of blood out of every stone, considered making a sequel to Snuff called The Slasher. This was exactly the kind of half-assed, unoriginal get-rich quick scheme he'd tried to run for years before getting lucky with a perfect storm clusterfuck. It also betrayed his profound lack of understanding of the forces behind the original film’s success.

But he was too distracted by a move to California and efforts to rebrand himself as a mainstream sci-fi and comedy producer to seriously pursue it. He focused on making a R rated sequel to a softcore porno, Revenge of the Cheerleaders, which he marketed using the tagline: Allan Shackleton presents A CHEERFUL FILM. It featured “an epic food fight wilder than anything seen on screen since the pie-throwing days of Mark Sennett… a youthful madcap farce.”

One morning in 1979, while he was out jogging, he dropped dead, the result of a heart defect he’d never told anyone about. The Snuff-fueled stress of the last few years had not done him any favors.

Without anyone to claim or denounce it, and with no credits to link it to anything beyond a swirling chaos of fear, misunderstanding, and rabble rousing, Snuff became an orphaned monster, lurking in the margins of American cultural consciousness. Whispers about a film showing a real murder circulating somewhere persisted into the 1980s, fueling panic about the dark edges of the porn world, and the violent perversions of voyeurism in general. Even after Snuff came out on home video and horror fans dissected its effects and history on early internet forums for all to see, taking the power out of the film entirely, the underlying idea of a movie like Snuff persisted.

The concept of snuff is still a staple of anti-porn rhetoric. A touchstone for modern, gorey horror filmmakers. And a lingering digital boogeyman that supposedly dwells somewhere deep on the dark web, in places internet conspiracy theorists call Red Rooms, where you can stream death on demand. This is why the film critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas calls Shackleton's Snuff the “most important ‘worst’ film'” of the ‘70s, and why it inspired academic conferences and collector's re-releases.

To date, no one has ever found evidence of a murder committed on camera to create widely-distributed, for-profit entertainment.